Originally published August 28, 2021 in The Austonia. Read the full text [here].

College football conference re-alignment and the controversial “Fair Pay for Play” ruling seems inevitable when you consider that eight of the top 10 biggest outdoor stadiums in the world host Saturday College Football games where the athletes on the field are paid $0. As a capitalist, I can get behind both of these concepts. As a former collegiate and professional athlete, I struggle mightily with their implementation and, importantly, with the reality that amateur sport as we know it will no longer exist.

Amateur football is a sport which touches most of our lives and shapes many of our communities. It brings us together for local Friday nights under the lights, tailgates and fan-filled stadiums and bars supporting our favorite teams on Saturdays. Students are likewise attracted to large public universities with winning football teams, and all benefit from the strong university programs supported by those revenues. To wit, the University of Texas Athletic Department transferred $12.2mm to the University for a range of services benefitting students and faculty alike last year, gapping a difficult time for all. We are all drawn to this uniquely American game of football for its complexity (as an aside, memorizing John Mackovic’s playbook was as hard as any class I took in the Business School at the University of Texas), elite athletes, and inclusive and electric environment.

At the university level, we all know that athletic departments struggle to turn a profit but for a successful football program, and it’s also arguably true that individual players can be behind certain teams’ iconic success. Think Vince Young and Johnny Manziel. In this context, I’m saddened by the reality that many great universities will be left behind if they don’t join one of what looks to be four power conferences, left with no ability to compete for big bowl games or championships – think Texas Tech where I have so many long-time friends. And, I’m conflicted by the reality that star players want more than they currently get from their college experience, which in most cases includes tuition, room and board, a fair living stipend and that intangible, hard-to-measure thing: a college education and a lifetime network.

To value what we can, let’s put a roughly $60,000 annual price tag on the measurable parts. State legislatures across the country are evaluating not if, but how athletes are to be paid for the use of their name, image and likeness (NIL), as well as how to hire agents and sign endorsement deals. There is currently no federal standard, creating an uneven playing field from state to state and university to university. Combine this with the recently approved player portal, which is the ability for NCAA athletes to freely transfer from one school to another without penalty, and potential abuse of the structure’s intent could run rampant.

I’ve always believed that the optimal solution here is to let any and all athletes go pro any time if they want to get paid, creating a true value proposition for the students and their sport. The reality is that the universities effectively serve as the minor leagues for the NFL, and the money in college football has pushed this ship far from the dock. I can also appreciate some of the arguments for paying college players. Advocates say that many are from low-income homes for which they are often providing support. While their NIL’s may be valued in the millions of dollars, many have reported living below the poverty line and are unable to take on a part-time job.

Those against direct payment for players point to a college education as being enough. The hard truth is that most college athletes will never make it to the pros, and those football players who do train mainly in the university setting. Meanwhile, many of these young adults will be busy building a social media presence rather than a resume that will help them compete for high-paying jobs that go to college graduates. Also, paying players will make the strong teams and the university systems they support stronger, and the weaker teams and colleges weaker. In other words, it further consolidates power in the hands of the most powerful, and with conference re-alignment underway, we should take pause. Maybe it’s all for the better. Maybe it isn’t. I am still thinking this through myself.

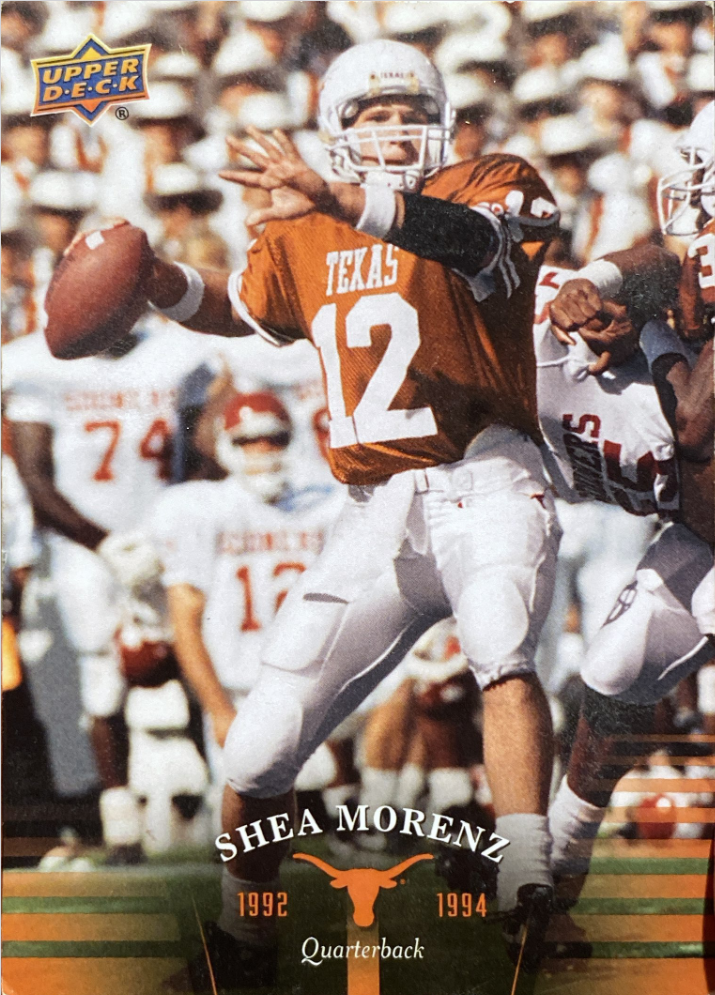

As a student-athlete, I played football and baseball for the University of Texas, and I had to keep up my grades to play. Despite being offered a potentially life-changing Derek Jeter-size signing bonus by the Toronto Blue Jays, I chose college over playing professional baseball straight out of high school. I would go back to that, but after my education was underway. My father made a similar choice, opting to play hockey at the University of Denver over professional hockey, which he eventually did. Education prepared us well for professional lives and not just lives in sports.

For the vast majority of student-athletes who are not lucky enough to make a career out of professional sports, the financial benefits of NIL sponsorships during college can be extremely attractive, albeit short lived, and may very well derail or, at the very least, dilute the focus on academics and job preparation.

This shifting world of the “athlete-student” model versus the “student-athlete” model is raising important questions: Just how professional should the traditionally amateur college sports world be? And what’s the appropriate age for professional marketers to approach our sons and daughters? I was honored to have Bill Walsh sitting on my couch recruiting me to Stanford as a high school senior, but I’m at a loss to consider the impact to my life if instead we were hosting free agents not associated with any school or education in our home starting much earlier. In situations like this, very young men and women could be pushed down a specific sports path, limiting their exposure to and involvement with other athletic, educational and social opportunities.

The NCAA has clearly lost control and, unfortunately, there does not appear to be a coherent plan coming from D.C. anytime soon. As college football becomes more professional and less amateur in this environment, we necessarily get away from playing because we want to … because we love our alma maters and are sharing with the student body a common educational experience. There is some purity and innocence lost. And in my view, it could take us one step, which leads to bigger steps, away from the love of the game.